Wi-Fi backscatter gives Internet connectivity to battery-less devices

Soon your wristwatch or any wearable device, will be capable of accessing Internet without requiring batteries.

Engineers at University of Washington have come up with a new communication system that uses radio signals as power source and then reuses existing Wi-Fi infrastructure to provide Internet connectivity to battery-free devices. Called 'Wi-Fi' backscatter, engineers believe the technology will play a major role in the evolution of 'Internet of Things'.

“If Internet of Things devices are going to take off, we must provide connectivity to the potentially billions of battery-free devices that will be embedded in everyday objects,” said Shyam Gollakota, a UW assistant professor of computer science and engineering. “We now have the ability to enable Wi-Fi connectivity for devices while consuming orders of magnitude less power than what Wi-Fi typically requires.”

The research will be soon published at the he Association for Computing Machinery’s Special Interest Group on Data Communication‘s annual conference this month in Chicago. The team behind 'Wi-Fi' backscatter plans to set up a start up company on the technology.

The new technology is based on an old research that had proven low-powered devices such as wearable devices or temperature sensors were capable of running without batteries or cords, by sourcing energy from radio signals in the air. The new research goes one step further by making it possible to connect these devices to the Internet.

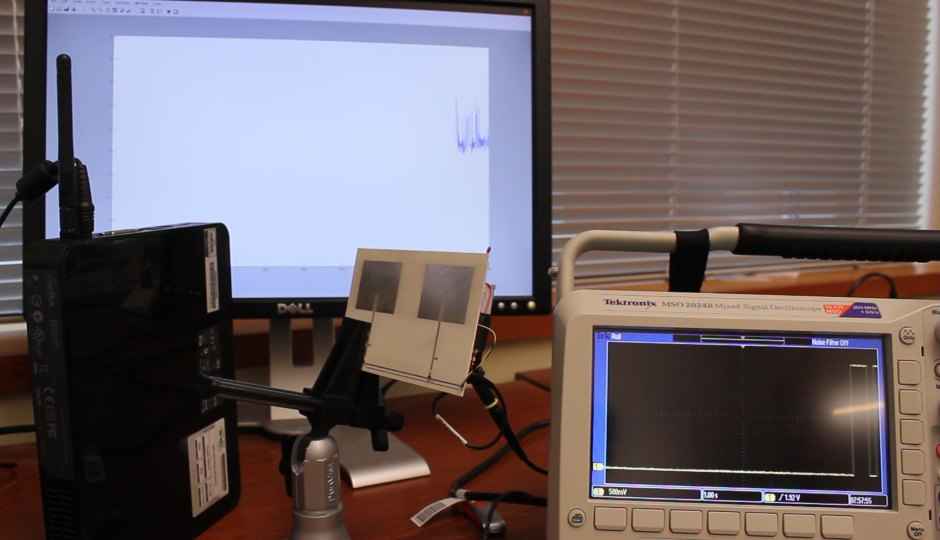

However, providing Wi-Fi connectivity had its own set of challenges, especially the power consumption. Researchers built an ultra-low power tag prototype featuring an antenna and circuitry that enables Wi-Fi devices without consuming a lot of power. The tags actually look for Wi-Fi signals moving between router and smartphone.

Researchers claim Wi-Fi backscatter tag can communicate with a Wi-Fi device at rates of 1kbps with about 2 meters between the devices. They plan to extend the range to about 20 meters and have patents filed on the technology.

“You might think, how could this possibly work when you have a low-power device making such a tiny change in the wireless signal? But the point is, if you’re looking for specific patterns, you can find it among all the other Wi-Fi reflections in an environment,” said co-author Joshua Smith, a UW associate professor of computer science and engineering and of electrical engineering.

Source: Washington.edu