Digitising the Gateway of India using laser scans and drone flybys

The Gateway of India to be preserved in photorealistic 3D, in a partnership between CyArk and Seagate, using technology like LiDAR, drones and photogrammetry

In a bid to preserve the cultural heritage and archaeological data about the Gateway of India, Seagate Technology has partnered with CyArk, an international non-profit dedicated to scanning and preserving similar monuments around the world. The scanning and archiving activity has started a couple of days ago and has already resulted in a lot of data and images being stored on Seagate drives. The scan data could potentially be turned into photo-real 3D models for students, tourists and heritage enthusiasts to explore the Gateway of India digitally. VR experiences like the ones on MasterWorksVR, a VR app for the HTC Vive, Oculus Go and Rift developed by CyArk that lets people visit heritage sites in VR. Whether the same will be possible for the Gateway of India is unknown at the moment.

Survey

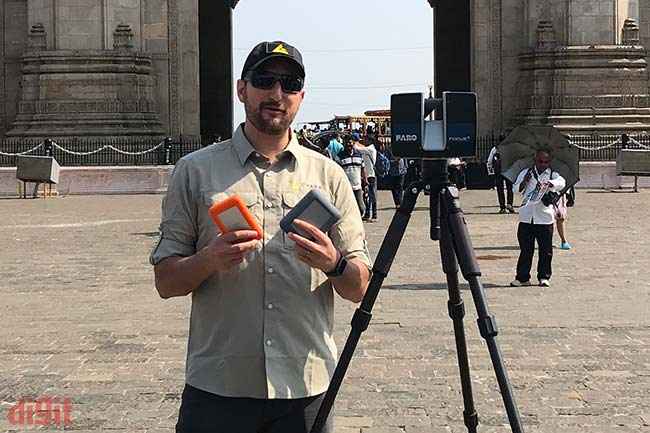

SurveyChristopher Dang, Field Director, CyArk at the site, with the LiDAR equipment and the Seagate LaCie drives

The technology

CyArk uses a three-pronged approach for gathering the data required for digital preservation. Photogrammetry, LiDAR scans as well as drones are used to cover every possible nook and cranny of the site with photographs and laser scans. This inevitably generates a lot of data. According to Christopher Dang, Field Director, CyArk, their scans over five days will generate anywhere close to 0.75 TB of data, comprising of, among other things, around 3000-5000 images and over 100 laser scans. This is where Seagate comes in.

With extensive requirements for storage space as well as durability, the Seagate LaCie drives have been particularly helpful for CyArk's work

As storage partner, Seagate is providing data storage solutions in the form of the LaCie Rugged Thunderbolt USB-C SSD, DJI Copilot, 2big Dock Thunderbolt 3, Seagate Nytro SSD as well as BarraCuda Pro 10TB. The DJI drone being used is the Phantom 4, which was operated by and availed from Quidich Innovation Labs. The LiDAR scanner being used is the Faro Focus which boasts of a 350m range. It has been sponsored by Faro, also a technology partner for CyArk.

The Faro Focus laser scanner

All of the data from the scans is then first used to create a 3D mesh of the site, without any photographs overlayed. Once the accuracy of the data has been verified and cross-checked, the same software overlays the photos based on the location data to generate the result. This is usually done across multiple systems in a distributed format to save time.

The DJI Phantom 4 flying overhead for a scanning run of the site (zoomed in-crop)

“Heritage sites are a significant part of humanity’s collective memory, but many of them are at risk from ravages of time. This year, we are excited to continue our partnership with CyArk and participate in this significant journey of cultural preservation in India”, said Robert Yang, VP of Asia Pacific, Sales at Seagate Technology.

The background

To understand how this project came to be, a little background on CyArk is needed. The company came to be in 2003 after Iraqi expatriate and civil engineer Ben Kacyra decided to invest his time and energy to document archaeological and cultural heritage resources. He was instrumental in the development of the first truly portable laser scanner in the 90s and the same tech is now seen everywhere in CyArk’s work. Since then, CyArk, with a 2-3 people field team, the overall strength of about 11, has documented over 200 sites spanning across 40 countries and 5000 years of human history, from Neolithic time period to something as modern as the Sydney Opera House. With Kacyra’s background in the Iraq War, where much of the country’s cultural heritage sites were damaged due to heavy looting and warfare, CyArk’s direction is to preserve cultural sites for future generations, but also comes to be helpful in certain different use cases.

CyArk's work on Mount Rushmore

For instance, in 2010, the Kasubi Tombs in Uganda were destroyed after a fire incident. However, one year prior to the incident, the tomb was documented and digitally preserved by CyArk in a partnership with Plowman Craven. This data is was then being used for the restoration of the site. Another similar instance is that of the Wat Phra Si Sanphet temple complex in Ayutthaya, where the CyArk team discovered that the temple spires do not align perfectly, with a lean of exactly 3 degrees, and highlighted the same to the authorities.

The process

Typically, for a project, CyArk goes through sources like UNESCO and the custodians to identify the needs of a particular site. After scans, site custodians could ask for orthographic data, true-to-scale models, flybys, virtual tourism and more. For instance, for the Gateway of India, the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Maharashtra, was interested to know the exterior elevation of the site. This data is necessary to identify erosion points, as one side of the monument faces the sea and is at the risk of erosion from sea water.

If you look closely at the lower half of screen, you can see the 3D data just scanned by device

For particular sites, there might be exceptions. For instance, the Gateway of India is a very sensitive site due to the presence of a naval dockyard, the Taj Hotel and multiple government offices and public buildings in close proximity. So, along with the standard permissions for drone operation from the local police, the on-site team of Christopher as well as Field Capture Specialist Avidan Fernandez also have to get their data checked by local authorities every day to ensure they have not captured any sensitive locations or infrastructure.

Initial processing results from the Gateway of India. This is a composite image of the point cloud and textured mesh.

There are multiple challenges involved in this process. For starters, the Gateway of India is a very popular tourist site and sees massive footfall every single day. Due to this, a number of scans have a lot of additional data points that are irrelevant for the site as they are generated off of people. Additionally, people could intervene with an ongoing scan by touching the tripod or the scanner, which, if moved even by 1mm, renders that particular run useless. Additionally, sunlight changes throughout the day, so the field team has to ensure that the visual data is captured in a way that shadow positions are consistent. However, the team performs relentless checks and takes multiple scans of every single position to ensure that these challenges to do not affect the final data.

While there’s no clarity as to how we’ll get to experience the digitisation the Gateway of India yet, there’s another project in India in the works which might see the digitisation of the Mysore Palace. As and when that happens, it is expected to be a bigger endeavour, however, as of now, it’s not entirely clear whether permissions have been granted or not.