Why India should take note of US ruling against Google’s anti-competitive practices

A recent US court injunction against Google has once again called out the Big Tech giant’s monopolistic activity, as antitrust scrutiny into Google’s marketplace behaviour continues to intensify.

After historic setbacks in antitrust cases related to its online search and advertising empire in recent months, Google’s now facing an unprecedented legal challenge to its Google Play Store policy – and why this matters for India as well.

Google ordered to do three key things

Earlier on October 7, US District Judge James Donato issued an injunction set to take effect on November 1, mandating significant changes to Google’s Play Store policies. The order stems from a legal battle with Epic Games, the creator of the popular game “Fortnite,” which successfully argued that Google was monopolising app distribution and payment methods on Android devices, violating antitrust laws in the US.

Also read: Google’s AI Summaries: Where everyone loses out. Eventually.

The injunction issued by the US District Judge requires Google to do the following things: Google should officially allow users to download apps from third-party platforms or app stores on Android devices, a practice known as “sideloading.” The US court injunction also prohibits Google from blocking the use of competing in-app payment systems.

Additionally, Google can no longer pay device manufacturers to preinstall its Play Store nor share revenue generated from the store with other app distributors. These changes are solely aimed at reducing Google’s excessive and overarching control over the Android apps and devices ecosystem, which the US court found to be unfairly limiting competition.

In response to the US court’s instruction, Google has argued that such injunctions could harm its business and raise security, privacy, and safety concerns within the Android ecosystem, according to a Reuters report. As of late October, Google has temporarily avoided major changes to its Play Store as a US federal judge blocked the original injunction in its ongoing legal battle with Epic Games, except one key point: Starting November 1, Google has been barred from tying payment or revenue-sharing agreements to exclusive Play Store pre-installation on devices. This restriction will be in effect for three years, ending November 1, 2027.

Google’s anti-competitive behaviour in India

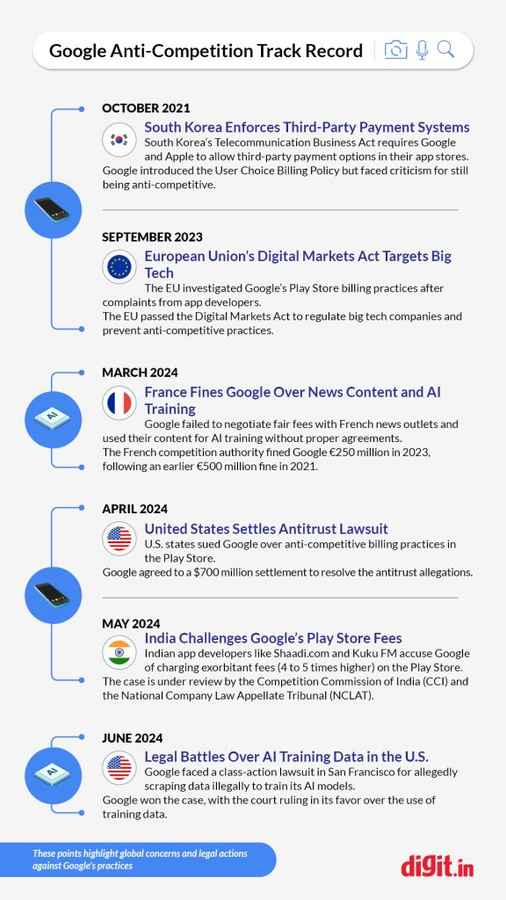

In India, similar concerns have been raised about Google’s dominance in the app distribution market. The Competition Commission of India (CCI) has previously fined Google for abusing its dominant position in the Android mobile device ecosystem. In October 2022, the CCI imposed a penalty of ₹1,337.76 crore on Google for anti-competitive practices related to Android mobile devices.

In March 2024, the CCI ordered an investigation into Google’s Play Store billing policies after Indian internet companies complained about the high commission structure, ranging from 11-30% on in-app purchases made by their users. For context, credit card payment fees generally range from 1-2%, while UPI transactions are free, making Google’s rates disproportionately higher, as per an Economic Times report. To put this into further perspective, affiliate commissions – which are typically paid for referring customers – range between 2-10%, depending on the category of purchase. This raises the question: why should App Store fees be so high when affiliate commissions are much lower? The companies which filed cases include Shaadi.com, BharatMatrimony, Kuku FM’s parent company Mebigo Labs, the Indian Broadcasting and Digital Foundation and the Indian Digital Media Industry Foundation, among others.

Also read: Google’s antitrust cases in India: A brief history

Subscription-based apps also face a double burden – Google charges approximately 30% on the first year of subscriptions and around 15% on renewals after the first year. Many app developers argue this is unfair, as companies should only be charged for discovery and distribution, not for future renewals. The industry sentiment is that a fair rate would be closer to 5%, particularly for long-term subscribers. Moreover, even if a customer uses UPI – where transactions are free for merchants – to pay for in-app purchases, app publishers are still charged these high commissions by Google, further amplifying the unfairness of the current system. In a 21-page order, the Indian antitrust regulator said it believes that Google may have violated the Competition Act and has decided to launch a detailed investigation into the matter. Although the investigation is ongoing, Indian companies have yet to receive compensation or any tangible relief.

Currently, there are few notable alternatives to the Google Play Store in India. However, options like GetApps and Galaxy Store exist but lack the scale and traction of Google Play. If the US ruling sets a precedent, India could witness more app stores entering the competition, offering developers a fairer marketplace.

In simple terms, Google operates the Play Store, the primary platform from which Android users can download apps. While Android is an open-source operating system, Google’s Play Store has become the dominant app distribution channel. Developers who wish to reach a wide audience often feel compelled to distribute their apps through the Play Store and use Google’s in-app payment system, which charges a commission on transactions. This has raised concerns about fairness, as developers argue they should not be forced to use Google’s in-app payment system for every transaction. Instead, they believe Google should only charge a referral fee for discovery and download, allowing developers to use their own payment processors for in-app purchases, reducing the financial burden on app creators.

Many developers and media companies are frustrated with additional restrictions such as Google’s prohibition on certain types of links and ads, including retail links for news apps. For instance, news apps are not allowed to include retail links without facing penalties or removal from the Play Store, limiting their ability to generate revenue through affiliate marketing or sponsored content. Similarly, media companies are barred from running certain types of ads that compete with Google’s ad services, further restricting their monetization options. These prohibitions have sparked criticism, with industry stakeholders arguing that such practices stifle competition and unfairly favour Google’s own services. This setup has been criticised for limiting competition and imposing unfair terms on app developers.

According to a June 2024 report, the Indian Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (MIB) held a meeting to discuss the imbalance in bargaining power between Big Tech companies and digital news publishers, with the latter being heavily reliant on the former for traffic and advertising revenue. The Digital News Publishers Association (DNPA) is believed to have advocated for a revenue-sharing mechanism with Big Tech companies, similar to Australia’s News Media Bargaining Code, France’s settlement with Google and Canada’s Online News Act. The meeting wasn’t conclusive on whether a legal framework is required to address the issues raised by news publishers or if a case-by-case redressal approach is better instead.

Impact on publishers and journalism

However, a new pressing concern is that AI-generated content and AI-driven search overviews are further killing publisher traffic by displaying answers directly to users, bypassing news sites altogether. This is seen as unethical, as AI systems are using publisher content without permission or compensation, raising large legal implications for copyright and content ownership. This practice not only undermines publishers’ revenue but also violates intellectual property rights, sparking calls for urgent legal measures to protect the rights of content creators in the digital age.

Additionally, Google’s increasing use of “zero-click searches” is compounding the issue. A zero-click search occurs when a user’s query is answered directly on the search results page, often through snippets, without the need to click through to the original publisher’s site.

According to Search Engine Land, a recent study by Semrush has revealed that nearly 60% of Google searches in 2024 resulted in no or zero-clicks. In the US and EU, over 50% of searches end without a user clicking on a result. While Google’s own properties receive a substantial portion of clicks, only 36% of clicks go to external websites. This suggests that a significant number of users are finding the information they need without leaving Google’s platform.

This practice is turning Google from a search engine into a content provider, significantly reducing the traffic that would otherwise go to publishers’ websites. The combination of AI overviews and zero-click searches is raising concerns about the future sustainability of digital media businesses.

By taking traffic away from publishers and disincentivizing them, there is a risk that publishers will start to look for alternative traffic sources, which may not be as reliable or lucrative as Google’s platform. This could lead to a reduction in resources for quality journalism, as publishers would have less incentive to invest in high-quality content if their revenue models continue to erode. Ironically, this decline in journalism quality would eventually affect Google itself, as lower-quality content would mean poorer search results, undermining the core value of Google’s search engine.

Indian legal experts weigh-in

Reacting to the ruling against Google by a US District Judge, cyber law experts believe similar ruling here would boost small developers and startup ecosystem in India, a digital economy dominated by US-based big tech firms.

“A ruling like this would foster an ecosystem where small developers and startups can compete fairly without being unduly burdened by the policies of dominant platforms. This is especially crucial for India’s startup ecosystem, where companies rely heavily on platforms like Google Play and Apple’s App Store to reach users,” according to Adv (Dr) Prashant Mali, a Mumbai-based practising lawyer and AI & Cyber Public Policy thought leader. “The Google vs. Epic Games ruling raises questions about whether consumers are being deprived of choice in digital marketplaces,” Adv (Dr) Prashant Mali further adds.

“The recent US court verdict is widely welcomed, as it opens the doors for fair and free market practices,” Adv Ashraf Ahmed Shaikh, Mumbai High Court, reacted while welcoming the injunction against Google, further explaining how “this verdict will prevent exploitation due to single monopoly.”

According to Adv (Dr) Prashant Mali, “India should take measures to ensure that users have access to a wider range of payment systems and platforms. This would encourage innovation, allowing smaller players to offer competitive services.”

It’s all about keeping public interest above private interest, or else Big Tech companies may become dominant and would interfere with the basic structure of liberty and freedom, warns Adv Ashraf Ahmed Shaikh. “This may give rise to authoritarianism and exploitation, therefore checks and balances are needed. No one should get a monopoly or else they start dictating terms. As we say absolute power corrupts absolutely,” says Adv Ashraf Ahmed Shaikh.

“With India’s digital market on the rise, regulations ensuring fair play for all developers can help local companies thrive. This can boost India’s goal of becoming a global tech hub by enabling homegrown businesses to grow without fear of being stifled by monopolistic practices,” says Adv (Dr) Prashant Mali.

Highlighting India’s Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP Act) of 2023 and Digital Competition Bill (DCB) of 2024, which aims to regulate digital enterprises and their practices to promote fair competition and protect Indian consumers, “India has already taken crucial steps in this direction,” sums up Adv Ashraf Ahmed Shaikh. India has taken crucial steps, but faster legislative and enforcement actions are needed to catch up with the rapidly evolving tech sector. Ultimately, though, is this enough to keep the power of Big Tech companies in check?

As the global conversation on antitrust regulations intensifies, Indian authorities have an opportunity to reassess and strengthen their policies to prevent abuse of market dominance and promote fair trade practices in the technology and media sector.

Also read: Google for India 2024: All eyes on AI

Jayesh Shinde

Executive Editor at Digit. Technology journalist since Jan 2008, with stints at Indiatimes.com and PCWorld.in. Enthusiastic dad, reluctant traveler, weekend gamer, LOTR nerd, pseudo bon vivant. View Full Profile