Watch porn online? Beware ransomware

Virtual sex is not always safe sex; you could catch a virus that shuts down your system.

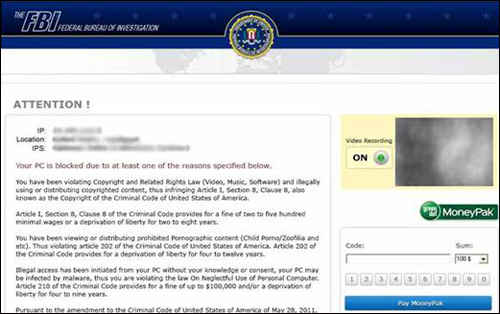

So a friend of a friend was watching porn online and contracted a nasty virus. No, not that kind of virus; we’re talking about ransomware. The malware often announces itself in a pop-up and (wrongly) informs a computer user that their machine has been commandeered by law enforcement for illegal activity. It will not be unlocked, the message says, until a fine is paid. Carriers are often porn sites, so victims are easily conned into believing the message is real. Whether or not the victim recognizes this for the scam that it is, their computer is unquestionably unusable until the virus is removed.

Survey

SurveyRansomware was first seen in Russia and Russian-speaking countries in 2009, according to the Symantec whitepaper “Ransomware: A Growing Menace.” The first known instance of the tactic came in a Cyrillic pop-up that claimed to be a message from Microsoft. It alerted the user that the computer had to be activated by the company before use by obtaining a code via an SMS message. That message was then sent to a premium rate number that charged the victim.

The perpetrators subsequently improved on their tactics—and profits—by going the shame route; a pornographic image replaced the Microsoft-branded one and its promised removal cost ballooned to around $460.

The next practical step was to move from shame to fear. In its current form, the malware generates a pop-up that purports to be from law enforcement and demands that the user pay a fine for illegal activity (most often an alleged viewing or distributing of illegal pornography) conducted on the computer. Lately, it’s taken the even more scaremongering tactic of speaking its message in the language of the victim’s country.

In its most recent incarnation, first reported by Trend Micro, the pop-up notification tries to validate itself by claiming that it’s under the aegis of a December 4, 2012 treaty between antivirus vendors and law enforcement to identify cyber criminals. Beneath the message are the logos of companies, such as Symantec, McAfee, Trend Micro, Microsoft, and ZoneAlarm. It’s even been masquerading as the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), a partnership of the FBI and the National White Collar Crime Center that filters complaints about scams such as ransomware to the appropriate authorities.

Hit-and-Runs

Even when the price is paid, the scammers will not restore the victim’s computer. Symantec notes that much ransomware does not even contain the code to uninstall itself. Forums are filled with stories of people who have paid the requested price and are still left with the virus.

On a Yoo Security forum, a commenter named Kevin writes, “I’m concerned. My laptop has been blocked with this FBI message since Tuesday evening. It won’t let me in unless I pay $400.00 via moneypak. I paid the $400.00 yesterday morning and the computer is still locked. Question? did my $400 actually goes somewhere, and how do I unlock this laptop.”

A YouTube video on how to remove the virus has a comment from Patriot2572, a victim twice over: “I paid the $300 and now it is requesting $600 after it was ‘rejected’ but i called moneypak and they said it the money was picked up by someone in Romania..

I sent the $600 now it is pending….”

The virus has even caused some to abandon their favorite sites. In October, online community SodaHead user my2cents announced to forum friends: “I’m just letting you all know that I am leaving SodaHead. About two weeks ago, my computer got locked by the FBI scam while on SodaHead…I can’t take the chance of that happening again, so I’m saying adios to SodaHead. I’ll miss you all, but keep up the good fight. And don’t let the bastards get you down!”

Visit page two to read Perp Walk, and Crime Does Pay

Copyright © 2012 Ziff Davis Publishing Holdings Inc

Perp Walk

While it is colloquially known as ransomware, the virus is called Reveton. It’s designated as a drive-by—catchable by just visiting a compromised site. Those sites are often porn sites, a fact that helps give credence to the displayed message that the user was engaged in illegal activity. Specifically, child pornography is often cited.

The scam is made even more believable because the virus is specialized, detecting the computer’s location and issuing a message that looks like it’s from a local authority. So U.S. victims will often see the FBI logo, while Canadians see that of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service and Austrians see the mark of the Austria Police.

Ransomware attacks victims all over the world. Malware researcher Kafeine and others maintain an ever-growing gallery of screenshots of its variants on botnets.fr. Symantec, in mapping two ransomware variants, has shown that relatively few countries are untouched. As Kafeine points out in a post, the virus quickly adapts to its surroundings, sometimes starting out with the look and language of, say, the U.K. variant and then quickly switching to the local language and the insignia of a local authority. Ransomware has recently found its way to Iran, which monitors and restricts the Internet for its citizens, undoubtedly making the message particularly frightening for victims and, thus, lucrative for the thieves.

Reveton locks the user’s computer. Even those not lured into parting with their money might find themselves unwittingly doing so. Reveton works with the Citadel malware platform, which can install other malware so that even after Reveton is removed, keystroke loggers can capture usernames, passwords, and credit card information.

Security blogger Brian Krebs reported that Kafeine, who runs the blog Malware don’t need Coffee, believes the Blackhole exploit kit is ultimately responsible. The software app works by taking advantage of security holes in browsers, Flash, and Java.

Symantec reports that there are around 16 ransomware gangs. The Metropolitan Police recently arrested three individuals in England: one man was charged with suspicion of conspiracy to defraud and another man and a woman were charged with suspicion of conspiracy to defraud, money laundering, and possession of items to defraud.

Crime Does Pay

The Symantec report states that “a conservative estimate is that over $5 million dollars a year is being extorted from victims.” Kafeine shared with the blog Krebs on Security screen shots of scam stats pages maintained by criminals. One scam netted about $34,500 in one day and $54,000 the next.

The ransomware price is often demanded in prepaid electronic payment form, meaning that there’s no chance for the victims to recover the funds once they realize they’ve been scammed.

Ransomware victims in the United States are primarily asked to pay by using MoneyPak. It’s an electronic payment system run by financial services provider Green Dot. MoneyPak is a natural choice for criminals since it’s widely available (MoneyPak prepaid cards are available at over 50,000 locations, such as CVS, Walgreens, and Walmart, across 49 states), virtually untraceable, and nonrefundable. MoneyPak lists the ransomware scam as the first one on its list of “Most Common Scams to Avoid.”

“Green Dot is committed to educating consumers about how to avoid being victims of financial fraud scams and works closely with law enforcement to help enhance these efforts,” a company spokesperson told PCMag. “In response to the FBI ransomware scam, Green Dot has partnered with the FBI and the Department of Justice’s Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Division to support their ongoing investigation.”

The MoneyPak site informs users that “[i]f you give your MoneyPak number or information about the purchase transaction to a criminal, Green Dot is not responsible for paying you back. Your MoneyPak is not a bank account. The funds are not insured against loss.” But nevertheless the spokesperson said, “Consumers are encouraged to immediately report fraudulent activity to Green Dot by calling 1-800-GREENDOT so we can attempt to recover any funds that have not already been removed by a scammer and can continue working with law enforcement to identify the origin of these activities and these abuses.”

Ukash, an offering from London-based Smart Voucher, has similar benefits and is often used in ransomware scams abroad. Instead of a prepaid card, Ukash is a 19-digit code that electronically substitutes for cash. It’s available at over 420,000 locations in more than 55 countries. It’s an excellent tool for thieves since money can’t be refunded once it’s spent, as Ukash’s terms and conditions state, “[o]nce Ukash has advised a Participating Merchant that a submitted voucher code and amount are validated, Ukash has no means of subsequently withdrawing such validation and the voucher code and amount will be considered redeemed and cannot be used again.” And the responsibility for verifying the credibility of a recipient of Ukash is on the Ukash user: “You cease to be the holder of the Ukash if you provide the details of the Ukash voucher code to some other person…whether such a person is acting unlawfully or is guilty of misrepresentation.”

“We are saddened to hear of people falling victim to scams involving fictitious products or services which ask for payment by Ukash,” David Hunter, CEO of Ukash, said in a statement to PCMag. “We take this very seriously as Ukash is designed specifically to help people shop safely online, removing the need to reveal personal financial details.”

Hunter said Ukash works with the police and also to educate the public, noting warnings about scams on vouchers and on Ukash’s website.

Often alongside the Ukash logo is that of paysafecard, a similar type of online payment. “paysafecard group is aware of the problem and is doing everything they can to prevent these attempts at fraud,” company spokesperson Ludger Voetz told PCMag. “paysafecard group works in close cooperation with the police, and support the police with their investigations, in order to stop the fraudsters.”

Voetz pointed out that paysafecard issued a press release last year as a warning to its customers. It reads in part: “The paysafecard group distances itself from these attempts and points out that public authorities, institutions, law firms, and courts do not accept paysafecard as a means of payment. paysafecard should only be used for payments at authorised online shops of official partners. Instructions to pay a fee or a fine by using a paysafecard should never be followed. Those affected should contact the police.”

Copyright © 2012 Ziff Davis Publishing Holdings Inc