Origins and the rise of DRM

We trace the emergence of Digital Rights Management (DRM) and how it has affected various forms of intellectual property historically

Intellectual property has always been a highly disputed area of law since quite a long time. From the point of view of a creator or designer, they do have the right to have a say in how their creation is utilised, due to the effort they have put into it. From the same point of view, they also believe that they deserve a share in any commercial gains made through their creation – directly or indirectly. On the other hand, if sharing and altering a creative idea or a concept can lead to the creation of something new and better, is it really fair to restrict the same?

In the technology age, everything from Digital Artwork to Music is created and marketed digitally. And to cover the ownership rights of the creator, there is the concept of Digital Rights Management, or DRM. Digital Rights Management technology refers to the tools that allow restrictions to be placed on copyrighted media and software applications to control their usage, (re)distribution and alterations. Now, there are arguments throughout history that fight for justifying this control and then there are arguments trying to convey that this entire concept is harmful to everybody as a whole.

The Early days

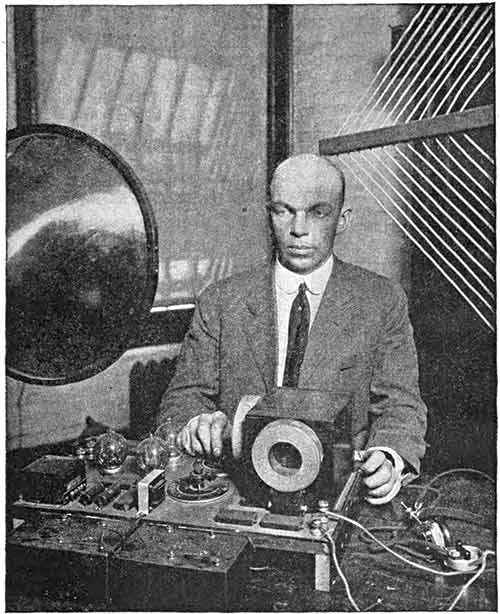

One of the most significant and earliest cases that can be put forward as a significant precedent regarding legal control over intellectual property is the invention of FM radio. One of the most significant problems in early day Amplitude Modulated (AM) radio broadcasts was static interference from external sources like electrical equipment and thunderstorms. Many inventors had tried in vain to find a way to overcome this limitation. Edwin Howard Armstrong was working for the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) when he formulated a method to successfully overcome AM radio’s limitations by modulating the frequency of the transmitted signal, giving rise to the FM radio technology that would eventually revolutionize the radio industry.

What RCA had asked him to work on was a way to filter out static. What he had invented was something that was a direct competition to RCA’s existing infrastructure and business. As a result, RCA had delayed further research into the same. Meanwhile, Armstrong was granted a patent for FM radio in 1933 and had performed successful demonstration after demonstration that showcased the never-heard before clarity that FM brought to radio broadcasts.

Knowing the potential of this technology, Armstrong took it to other players in the market like Zenith and General Electric. He also heavily lobbied the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to create an FM broadcast spectrum between 42-50MHz and himself invested in creating a small but high-powered network of FM radio stations to truly broadcast the superiority and promote the adoption of FM. But the RCA had other outcomes planned for FM.

Edwin Armstrong was one of the first victims of a major corporation misusing laws in the spirit of DRM

RCA had hired a former head of the FCC before the second world war broke out to deter the spread and adoption of FM. Although their pre-war efforts were largely unsuccessful, during the war the nation was largely preoccupied with other matters and it was no surprise that when the war ended, the FCC came out with a number of regulations that effectively crippled FM. Citing flimsy reasons and unreasonable potential technological problems, FM was forced to move to a higher band, which rendered the existing FM stations and devices useless. Regardless to say, the public, once burned with their now useless FM radios, was further hesitant to get new devices for the new bands and the arrival and propagation of television sealed FM’s fate. After a number of drawn out expensive lawsuits, Armstrong ended his own life. Proprietary interests had completely obliterated the good intentions of a true innovator.

One of the earliest instances of copyright laws was the adoption of the first copyright act by the British Parliament. Known as the Statute of Anne, the law stated that the copyright of any author over their own book was valid only for 14 years, and had to be renewed after that if the author was alive. And this law was much less powerful than the ones we are familiar with now – it did not restrict adaptations, translations and derivative works of any kind. At that point of time, copying and piracy was not a major concern mainly because copying and publishing was an expensive thing to do and was only handled by major publications.

Forget your peers

Fast forward to the present day – the internet has become the universally accepted medium for exchange of information of any kind. And as a result, it is much easier to violate copyright now than it has ever been. The basic nature of digital information entails that any kind of digital information can be copied now with highly easy-to-use methods and often require no expertise of any kind in the field of work that the original information deals with. As a result, there are DRM regulatory technologies that are sometimes strict enough to inconvenience genuine users.

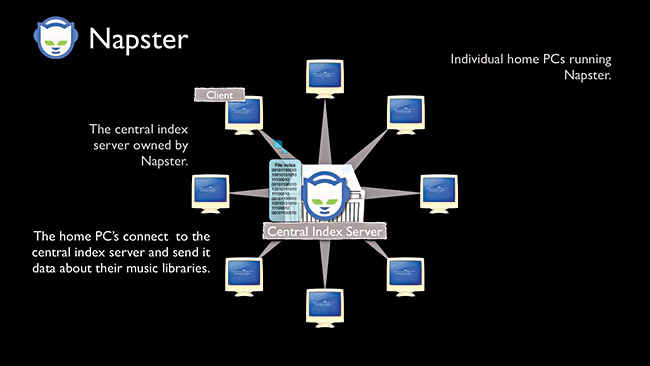

Since the advent of internet, a new form of file sharing had emerged – peer to peer(p2p) file sharing. Even though the technology might have evolved over time, the basic principle is still the same – having access to files in a network of connected computers connected via a central server at a large scale. Even though the technology of file-sharing was in place for a while, it was truly popularised at the turn of the century by Napster.

Napster worked by indexing the connected computers using a centralised server

Napster was started by the then 15 year old Shawn Fanning in his university first year as a network that allowed connected users to download compressed digital music files, especially MP3, from any machine on the network. What popularised it compared to other p2p services is that Napster used its central server to index the music on connected users’ machines and made the data searchable across their network. And what popularised it even more was the landmark lawsuit that went on to set a standard regarding intellectual property: A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc. In course of the lawsuit, Napster cited many defences (inability to differentiate between files that did and did not violate copyright, encouragement to file sharing by digitizing music in the first place etc) that were struck down one by one accusing Napster of insufficient policing. In September 2001, Napster agreed to settle the case by paying $26 million and by May 2002, Napster had filed for bankruptcy, thus ending its first incarnation. This set the precedent that any unregulated peer to peer file sharing is illegal and harmful to the original copyright holder.

Hence it hasn’t been anything surprising that technology has been repeatedly outpacing the law that governs it in terms of copyright infringement. The MGM Studios vs Grokster case in 2005 is considered by many to be the sequel to the Napster case. Filesharing services like BitTorrent and torrent sites like PirateBay have been facing long legal battles but the opposition has so far been unable to shut these services permanently, thanks to very freedom and anonymity that internet stands for.

All these locks

DRM currently comes in many shapes and sizes. For example, for computer games alone, there have been multiple forms of DRM. Another notable area where DRM has a strong-ish hold is eBooks. Adobe, Amazon and Apple that provide the software and the backend infrastructure to support the entire publishing process have their own DRM methods that are designed to restrict copying, alteration and exchange of ebooks from their proprietary devices or applications. In one of the most significant examples in recent times, in July 2009 Amazon remotely deleted copies of George Orwell’s Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty Four from customer’s Amazon Kindles and offered them a refund. Amazon cited the reason as copyright violation because the company that was publishing and selling the books on Amazon’s platform did not have the rights to do so. They couldn’t have chosen a more perfect book right?

The music industry has contributed significantly to the progress of DRM technology. After initial compatibility issues with CDs that came with DRM technology, in 2005 Sony BMG included new DRM technology into their CDs that covertly installed DRM software on the users’ computer without explicitly asking for their permission. Along with the obvious issues with this, the software also included a rootkit that introduced a security vulnerability that could be easily exploited by others. Eventually, Sony had to recall most of the CDs that included this software and provide a cash compensation or a free album download to users.

DRM and Music Streaming

With the rise of music streaming in the later 2000’s, there came the need for newer forms of DRM. Perhaps the most popular music content provider at the time of its inception, Apple’s iTunes worked with its own FairPlay DRM that allowed music obtained via iTunes to be only played on Apple devices and Apple’s Quicktime Player. Apple even launched a higher quality iTunes Plus format in May 2007 that could be obtained at a higher price.

Napster, in its second incarnation also adopted DRM tech. Their method allowed the user to stream an unlimited amount of music while the subscription was valid by downloading the music in WMA format. When the subscription expired, all downloaded music was made unreadable until it was renewed.

Label proposed by the Free Software Foundation for DRM free works

The keys to the locks

One of the most recent testaments to DRM was Steve Jobs’ ‘Thoughts on Music’ open letter back in 2007. In the essay, he cited the requirements of music labels as the only reason why iTunes was still persisting with DRM. In his words –

“Imagine a world where every online store sells DRM-free music encoded in open licensable formats. In such a world, any player can play music purchased from any store, and any store can sell music which is playable on all players. This is clearly the best alternative for consumers, and Apple would embrace it in a heartbeat.”

Meanwhile, Apple itself has been on the receiving end of an antitrust lawsuit that accused its iPod devices and iTunes of quashing competition by preventing any other music store from working on their platform.

Even at present, DRM remains one of the most highly debated technologies in the world of content sharing. Either the proponents of intellectual property get to assert their right with the content and impose stricter regulations, or the activists against DRM get to convince the law that the harm which DRM causes to legitimate users is far more than the harm caused by illegitimate users. The true answer to the DRM conundrum shall always be an elusive balance that allows valid cases of reproduction and attribution without robbing the original creator of the benefits that they deserve.

This article was first published in the March 2016 issue of Digit magazine. To read Digit's articles first, subscribe here or download the Digit e-magazine app.