Bandersnatched: The origins of interactive storytelling and branching storylines

Do you think Netflix's Black Mirror film Bandersnatch is the first of its kind? You need a nosedive into the entire history of interactive storytelling.

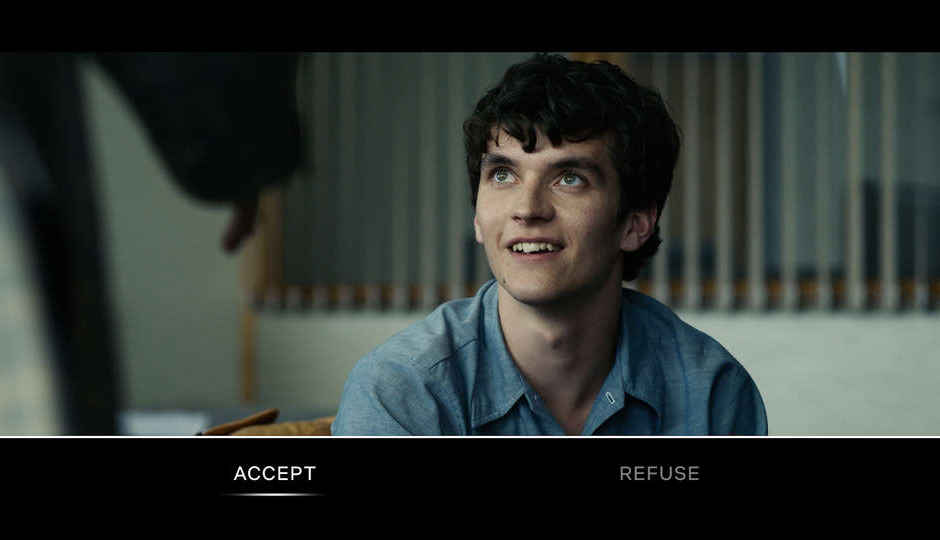

Have you seen Bandersnatch yet? In December 2018, Netflix released the latest entry into its anthology series Black Mirror in the form of Bandersnatch, an interactive movie where you get to make decisions for the characters as the story goes. While the storytelling itself deserves a mention, it’s the format itself and the ability to influence the characters’ lives that has made people go crazy about it. Well, that and the completionists hell-bent on exploring all possible storylines. Don’t believe us? [SPOILER LINK alert] There’s proper flowcharts being made out there, people!

Survey

SurveyHowever, a large number of people are under the impression that this is the first time interactive storytelling has been attempted. The truth is, it is not even the first interactive movie to be made. It’s more than half a century too late for that milestone. Surprised? How about the fact that interactive storytelling has existed since time immemorial?

How interactive entertainment is ancient

If you think about it, we’ve been enjoying interactive entertainment for ages now, as a civilisation. Theatre plays, operas, sports and quite a few other forms of entertainment have traditionally been quite interactive, with the audience cheering, booing, and if it's really bad, even throwing stuff at the performers. While this wasn’t really about picking a direction for the story, the instant and direct expression of audience reaction cannot be ignored as a form of interactivity.

The earliest known examples of theatre venues, where the entertainment was literally surrounded by its audience, date as far back as 4th century BC

While this might seem insignificant to you now, but you have to understand that our entire collective cultural history has been in this form. It is only in the 20th century that this changed with the advent of radio, and subsequently, television. Sure, you might have screamed at your TV when your favourite character was killed, but they definitely didn’t get affected by that.

However, it wasn’t just restricted to being present for the performance or reacting to it. Some early instances of interactive storytelling actually did let the audience participate. Back in 1936, Night of January 16th, a play by Ayn Rand that was initially titled Woman on Trial, let members of the audience play the role of the jury in a murder trial; the play would proceed on to one of two narratives depending on the verdict. However, the first gamebook, which is what books with interactive storytelling are called, predates the play by four to six years.

Gamebooks a.k.a choose your own adventure

Back in the 60s, somewhere on the other side of the world, a father was telling bedtime stories to his daughters when he ran out of ideas. Not knowing what to do, he decided to ask them what Pete, the protagonist, should do next on the isolated island he was on. The next thing he knew, his daughters were enthusiastically suggesting one option after another as he crafted multiple storylines for Pete that night. That very same night, Edward Packard picked a particular storyline for himself as well – that of turning this idea into a successful book. The Adventures of You on Sugarcane Island, written in 1969 and released in 1976, went on to spawn the popular Choose Your Own Adventure (CYOA) series that published more than 60 titles.

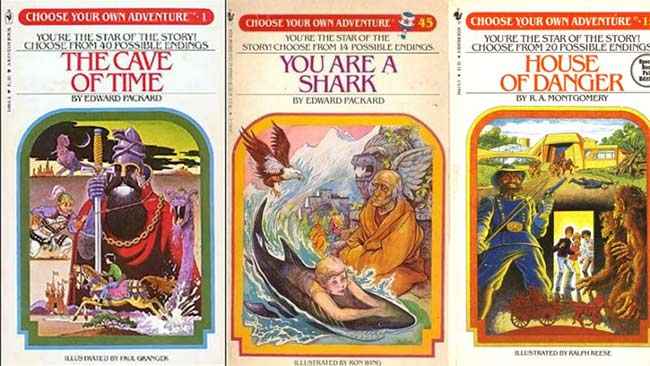

A few examples of the Choose Your Own Adventure series

However, the earliest known gamebook came out almost forty years before that. Consider the Consequences! by Doris Webster and Mary Alden Hopkins not only predates Packard’s work, but it also predates what has been considered to be the first visualisation of CYOA genre stories by almost 75 years. On the other hand, the genre was quite popular in other languages even before CYOA arrived officially, but gained mass popularity in the 80s with CYOA. However, the fate of interactive storytelling was headed down a branch that would take it to the domain of moving pictures.

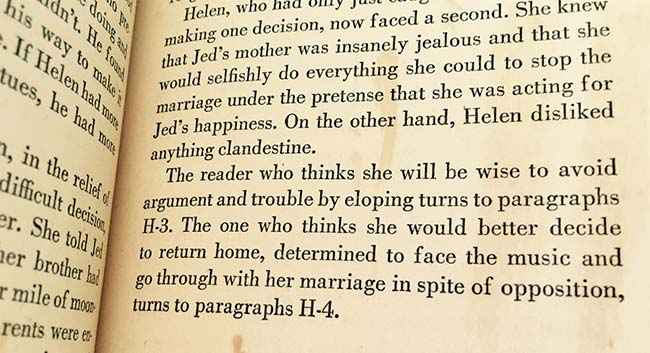

A paragraph from ‘Consider the Consequences’ showing how the story handled branching.

The merging of video and gaming: Interactive movies

There wasn’t any major role for technology in interactive storytelling until someone decided to put it up on the big screen. The 1967 movie, Kinoautomat, is often cited as the first example of interactive cinema. In its initial screening, the audience was seated in a theatre where every single one of the 127 seats had a pair of buttons. This had let the audience make decisions, led by the narrator, at nine crucial points in the storyline. There were essentially two cuts of the film which converged in the narrative at nine points, where the choice was brought to life by simply switching the lens cap between two projectors running each cut separately. Innovation in this medium was fairly limited at that point, and apart from a similar project in 1992, there weren’t too many interactive cinemas until recently.

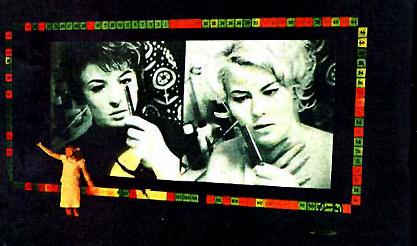

How 'Kinoautomat' handled interactivity. The red and green indications around the screen show how the voting went, with each light representing one vote.

On the other hand, innovation was underway in another area. Games of the same era suffered huge limitations in terms of graphics and looked towards using the vast storage capacity of LaserDisc and live-action or animated video to overcome the same. With a conceptual first in 1974’s Wild Gunman from Nintendo, what made these games a part of the interactive storytelling camp was the multiple storylines playing out depending on user actions. Notable names include Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace. Interestingly, the first known example of a cutscene in a game was from Bega's Battle, also released around the same time.

If you just can’t recall where you’ve seen 'Dragon’s Lair', we’d suggest you rewatch 'Stranger Things' Season 2.

While the novelty factor of such games/interactive movies was beginning to wear off by the 80s, innovation was far from over. Working for Atari founder Nolan Bushnell’s new company Axlon, Tom Zito and his team would go on to develop NEMO, a platform that ditched LaserDisc for tape. This allowed players to switch between multiple interleaving video streams, similar to switching channels. However, the world of gaming would be destined for far more interactivity.

Branching storylines in games

While there’s a lot of debate about the exact definition of interactive movies, the extent of branching storylines through interactivity that eventually became possible in gaming renders the debate inconsequential. The rising popularity of personal computers, consoles and the internet in the 90s made people more conducive towards experiencing all kinds of stories, especially interactive ones, from the comfort of their homes. When it comes to gaming, branching storylines are mostly seen in two primary formats – visual novels and RPGs.

A screenshot from Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors, a recently acclaimed visual novel

Visual novels are more interactive than CYOA books and interactive movies, but less than full-fledged games. As a format, it is widely attributed to have originated in Japan, and usually features dialogue and other decisions usually taken on static screens, although animated versions are known to exist as well. Recent notable examples include Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors and Zero Escape: Virtue's Last Reward. Both feature multiple endings and take into account decisions taken earlier in the game to determine player actions later.

RPG games with branching storylines differ from visual novels only in the fact that they contain more RPG elements, like character selection, quests and more. These factors also influence the branching storylines. Might and Magic VII: For Blood and Honor (1999) would be an early, but quite limited, example, falling short of more stellar options such as Star Ocean: The Second Story, released for the original PlayStation in 1998 with as many as 86 possible endings! Over time, recent games like the Elder Scrolls series, Mass Effect series, Dragon Age series and more have had player choices influence game experience not only during the current game but even in the sequels being played on the same system or with the same profile.

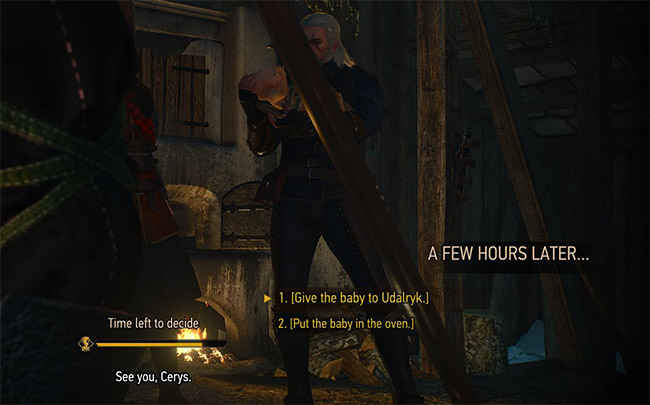

Titles like 'Witcher' are known to have decisions that also affect your gameplay in sequels, and there are many games that take this to the next level

Future of interactive storytelling

Pitting gaming against other forms of media when it comes to interactive storytelling is not only unfair, it is not required. Gaming isn’t on the cusp of a transformation with this format like how video is. For reasons too widely known today, people are consuming more video content than ever – on their laptops, smartphones and multiple other screens around them. These devices offer a unique opportunity beyond television and movie theatres. Audiences are typically used to placing themselves in front of a TV or a movie screen and doing nothing. On the other hand, our experiences with smart devices are usually more interactive.

If Netflix’s Bandersnatch wasn’t a first, it could definitely be a turning point. It has brought this format to a large audience that is not limited by familiarity with gaming, or an affinity for books. The future of entertainment is not necessarily interactive, but with technology like gaze detection, gesture control, voice control, combined with virtual reality we could be looking at one where interactive storytelling is more immersive. In the near future, you could not only be at the centre of the action, but you could also be controlling it. At what point does it stop being a movie and become a hyper-realistic CYOA game? When you find out, let us know at editor@digit.in.