Chris Solarski on the art of game design

Shedding light on some of the artistic side of gaming is a veteran of the industry. Following is his unique insight into the world of video game art and design.

Besides captivating plots and intricate storylines, the world of video games is a pandora of visual stimulus, full of memorable characters and breathtaking landscapes. Bringing all of them to life in order to leave a long-lasting impression on the gamer’s mind takes talent and skill. Shedding light on some of the artistic side of gaming is a veteran of the industry. Following is his unique insight into the world of video game art and design.

Q) How did you get sucked into the world of videogames? Were you a nerdy, game-oholic growing up as a kid?

I’ve been playing games since the days of the ZX Spectrum. However, I wouldn’t say that I was ever a game-oholic. Games tended to be very difficult back then—requiring a lot of dedication and repeat plays to complete. I enjoy games for their powerful escapism so whenever a game became too difficult or competitive I would give up and go do something else. I include here games like the original Super Mario Bros., and Mega Man 2 for the Nintendo Entertainment System—games I loved immersing myself in but ultimately found to be too frustrating. Thankfully games are now more forgiving and offer more varied gameplay experiences.

Q) Your all-time favourite games? Past and present? Why?

There are many games, so I’ll name the two that first come to mind: The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, and Halo: Combat Evolved.

I loved playing Zelda OoT primarily because of the dungeons. Each puzzle was so elegantly designed that the game still stands up as a masterpiece to this day. Additionally, Zelda OoT’s expansive world and rich set of characters made it very easy to become immersed and lose track of time.

Halo: Combat Evolved was the reason why I bought an XBox after seeing fellow students play through a level at university. Level designs that allowed for multiple routes, strategic weapon selection, and believable AI altogether contributed to the feeling that I was inhabiting a living, breathing world. There were also fewer cutscenes in this first Halo game, which left more room for me to create my own stories—something that got lost in the sequels, which became increasingly more complex.

Others video games worth mentioning include ICO, Portal 2, Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP, Journey, Gone Home, Ghost Trick: Phantom Detective, Broken Sword, and Resident Evil 2.

Q) What made you opt for gaming as a career choice? Was it a hard choice to make?

I studied computer animation at university, which I initially got into because I wanted to be an animator at Pixar, or some such studio. I later developed a passion for games after reading issues of EDGE magazine (sometime around 2002), which was the first time I’d heard anybody treat games as something worthy of critical discussion. I realized that games are a medium with a lot more artistic potential than I’d previously realised. The decision to commit to a career in game development was easy, since digital entertainment is a very exciting and rewarding industry to work in.

Q) Is there a difference between game design and game art? Which one do you like better?

Yes, there are differences between the two disciplines however their responsibilities overlap and should not be designed independently—especially in the context of story-driven video games.

Consider a game like Nintendo’s Super Mario Bros. A game designer, for instance, thinks about Mario’s speed, how high he can jump and the shapes of his jump arcs. Such rules and mechanics determine which ledges Mario can reach and the overall challenge posed to the player in successfully navigate the game’s levels.

These game design choices simultaneously affect how players perceive Mario’s personality. His bouncy and energetic movements create an impression of up-beat positivity. If gameplay dictated that Mario should move with more angular, slashing gestures, his perceived personality would be altered to something closer to Ninja Gaiden’s vengeful, Ryu Hayabusa.

For story-driven games to reach their full artistic potential, game designers and game artists must work closer together. Better still is to have hybrid designers—like thatgamecompany’s Jenova Chen—lead projects, by designing games around aesthetic experiences. This is the position I like to take, and why I describe myself as an Artist Game Designer. I see game design and game art as equals, although I feel more at home with game art.

Q) Who should become a game artist? How does one determine that they possess the right aptitude to be a game artist?

I firmly believe that everybody can become a great artist. The determining factor is passion.

Becoming a great artist takes years of practice. Along the way you’ll likely feel like you’re not progressing, and wonder whether you’ll ever succeed. If you have a passion for making art, you’ll push through these disheartening thoughts and continue purely for the love of the creative experience. Just keep in mind that creating great art is a struggle that every artist, at every level, experiences. If you’re ever in doubt whether to keep going, ask yourself whether there is anything else you’d rather be doing!

Q) What are some of the fundamentals of game art / game design that every artist should remember?

It’s important to see yourself as an artist first and foremost, that happens to specialize in game art. Despite their high-tech capabilities, games are essentially an accumulation of traditional artistic disciplines orchestrated through game design.

It is therefore vital that you study traditional art and design techniques from various creative fields outside of gaming. Disciplines like traditional painting have been around for over 2000 years, so there are many valuable lessons that we can apply to video games—a medium that is less than half a century old.

Q) Form follows function. How true is this in the case of game art?

This certainly holds true in video games, and is reflected in the prototyping stage of development where the whole team works together to block-in the entire game using simple game objects. Designing characters and environments should begin only once you’ve established which game elements are necessary and what function they have in the game. Otherwise you may waste a lot of valuable time and resources designing something that has no relevance to the overall experience.

Game artists must therefore be prepared to work on an abstract level (creating placeholder boxes, for instance) during early stages of a game’s development and do the “fun” stuff once the game’s framework direction has been decided.

Q) Should a budding artist hone their skill with a pencil and paper or should they work directly on digital devices or platforms? Why?

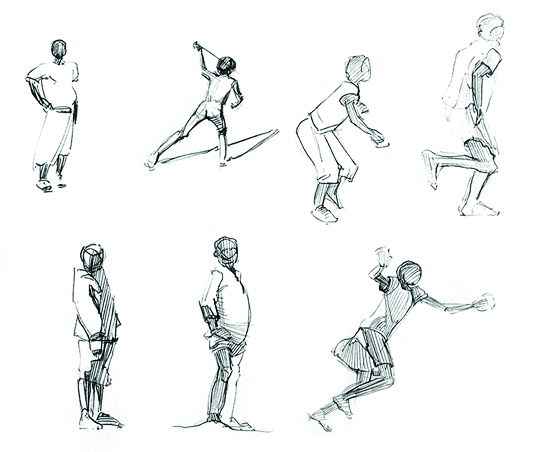

I strongly recommend pencil and paper, and traditional painting for honing skills. This is because drawing with a pencil is a direct experience, which helps artists to experience the subtleties of expression and movement without an intermediate interface. What you draw is what you get!

While digital devices are an abstraction of traditional media, so the process is less direct because you have to manually adjust settings to achieve effects that would otherwise be intuitive. Digital software also makes it easier to make artwork appear more impressive than it actually is using various special effects and tricks.

If you can draw a convincing person using nothing more than a pencil and paper, you’ll have no trouble achieving the same effects using digital media.

Q) Why do games like Borderlands, Prince of Persia, BioShock, etc, leave a lasting impression on players’ visual sense of appeal better than most others? And how big a part does visual brilliance play in determining a game’s overall success?

I mentioned earlier that games—story-driven games in particular—are essentially an accumulation of traditional artistic disciplines orchestrated through game design. So I think the success of games like BioShock is largely down to highly skilled teams that excel at getting the game designers, artists, programmers, musicians, writers, etc. all working harmoniously together towards a singular artistic vision.

Q) Couple of years ago, you published a book on game design and art. What prompted you to do this? How was the experience, and what’s your ultimate objective with the book?

Yes, that’s right. Drawing Basics and Video Game Art: Classic to Cutting Edge Art Techniques for Winning Game Design was published by Watson Guptill in 2012. The book’s primary function is to highlight links between classical art and video games. Drawing Basics and Video Game Art features drawings by artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, and Michelangelo to illustrate how the Old Masters created the sensations of depth, movement, energy and emotion and how we can adapt their techniques to more create emotionally-varied and meaningful video game experiences.

Although the book is aimed at game artists, my ultimate objective was to put forward a common design language that the whole development team can relate to. I did this using the concept of primary shapes—the circle, square and triangle—and their associated emotional value. You’re welcome to read my article on Gamasutra titled, The Aesthetics of Game Art and Game Design, to get an introduction to these concepts.

Q) You were in the country recently. What’s your impression of India as a game development destination? What unique contribution can Indian artists make to the global tapestry of gaming as an industry?

Yes, that’s right! Thanks to the kind support of the Swiss Arts Council, Pro Helvetia, I was in New Delhi to conduct a character design workshop at AnimeCon India, and the AJK Mass Communication Research Centre. It’s my first time in India and it’s been a pleasure meeting local developers like SuperSike Games, and Ninja Chip Studios who are hard at work developing high quality indie titles.

The game development industry in India is surprisingly similar to that of Switzerland’s, consisting of a small community of young studios with a strong passion to bring gaming to bigger audiences. Something that the small country of Switzerland could never support, though, are the big AAA studios that deliver outsourced work to overseas companies.

Independent developers, in particular, have plenty to offer the global industry because the culture is so unique and historically rich. I believe developers should take what they need from the AAA industry abroad, while also embracing their own culture. They can think of themselves as pioneers in a country that has yet to realize the full potential of games. There are certainly enough Indian consumers who, I am sure, would be excited to play games with a local flavor.

Q) Any advice for young game designers out there who want to make a career out of their passion?

Talent is 90% hard work. To become a “talented” artist it’s important to draw as much as possible—ideally at least once every day.

Admittedly, it’s sometimes difficult to find the motivation to draw frequently because artists tend to set high expectations for themselves when creating original artwork. So when you’re low on energy a great alternative is to make pencil studies of artwork that you like. Doing so lowers the pressure, and also serves as a free education by way of actively analyzing the process of your favorite artists. Some of their talent is sure to rub off on you.

Another way to motivate yourself and keep your energy up is to take part in game art competitions, and by offering to help friends with their projects. This will commit you to delivering artwork for real deadlines—experience that will come in handy when you land your dream job in game development! Without deadlines it’s easy to spend weeks, months or even years procrastinating. Don’t worry too much about whether you think you’re already good enough. The challenges you overcome and the lessons you learn along the way are what counts in the end. All the best!

Biography

Chris Solarski is an “indie academic,” artist game designer and author of the influential book, Drawing Basics and Video Game Art: Classic to Cutting Edge Art Techniques for Winning Game Design (Watson Guptill 2012). Chris has given talks about the intersections between videogames and classical art, animation, and film at various international events and institutions including the Smithsonian Museum's The Art of Video Games exhibition, SXSW, USC Interactive Media Division, FMX Stuttgart, and Game Developers Conference. He received a BA in computer animation and began working as a 3D character and environment artist for Sony Computer Entertainment in London. Eventually, Chris enrolled in art classes at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, where his interest in cross-disciplinary techniques to video games began. Chris has begun developing his own video games under Solarski Studio with the aim of exploring new forms of player interaction and creating more expressive and varied emotional experiences in games.

Jayesh Shinde

Executive Editor at Digit. Technology journalist since Jan 2008, with stints at Indiatimes.com and PCWorld.in. Enthusiastic dad, reluctant traveler, weekend gamer, LOTR nerd, pseudo bon vivant. View Full Profile