Android Application Development and Optimization on the Intel Atom Platform

This paper introduces detailed methods for developing and porting an Android application on the Intel Atom platform,

This paper introduces detailed methods for developing and porting an Android application on the Intel Atom platform, and discusses the best known methods for developing applications using the Android Native Development Kit (NDK) and optimizing performance. Android developers can use this document as a reference to build high quality applications for the Intel Architecture.

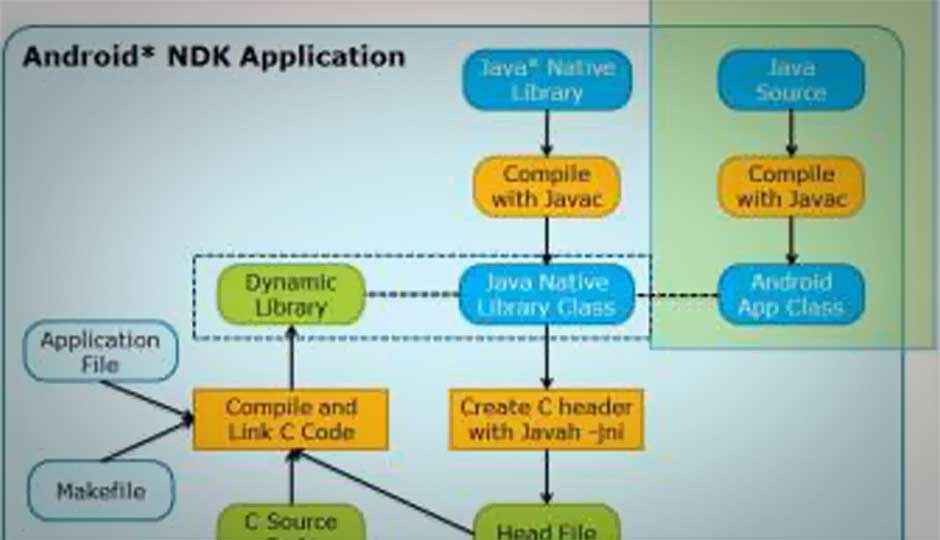

Android applications can be classified into two types as shown in Figure 1.

-

Dalvik applications that include Java* code and use the Android official SDK API only and necessary resource files, such as xml and png, compiled into an APK file.

-

Android NDK applications that include Java code and resource files as well as C/C source code and sometimes assembly code. All native code is compiled into a dynamic linked library (.so file) and then called by Java in the main program using a JNI mechanism.

Figure 1: Two types of Android applications

2.1 Introduction

The Android Native Development Kit (NDK) is a companion tool to the Android SDK. The NDK is a powerful tool for developing Android applications because it:

-

Builds performance-critical portions of your applications in native code. When using Java code, the Java-based source code needs to be interpreted into machine language using a virtual machine. In contrast, the native code is compiled and optimized into binary directly before execution. With proper use of native code, you can build high performance code in your application, such as hardware video encoding and decoding, graphics processing, and arithmetical operation.

-

Reuses legacy native code. C/C codes can be compiled into a dynamic library that can be called by Java code with a JNI mechanism.

2.2 Tools Overview

During the development period, you can use the Intel® Hardware Execution Manager (HAXM) to improve Android simulator performance. HAXM is a hardware-assisted virtualization engine (hypervisor) that uses Intel® Virtualization Technology (Intel® VT) to speed up Android application emulation on a host machine. In combination with Android x86 emulator images provided by Intel and the official Android SDK Manager, HAXM results in a faster Android emulation experience on Intel VT-enabled systems. To get more information about HAXM, visit: http://software.intel.com.

2.3 Installing HAXM

Use Android SDK Manager to install HAXM (recommended), or you can manually install HAXM by downloading the installer from Intel’s web site. If you want to update it automatically, please install it using Android SDK manager as shown in Figure 2. [1]

Figure 2: Install Intel HAXM using Android SDK Manager

You can also download an appropriate installation package from http://www.intel.com/software/android to your host platform, and then follow the step-by-step instructions to install it.

2.3.1 Set up HAXM

The Android x86 system image provided by Intel is required when running HAXM. You can download the system image using Android SDK Manager or manually download it from the Intel® Developer Zone website.

After images install successfully, Intel® x86 Android emulator images are automatically executed using the “emulator-x86” binary provided with the Android SDK. The Android emulator is accelerated by Intel VT, which speeds up your development process.

3.1 Developing NDK Applications for Intel Atom Processor-Based Devices

After successfully installing the NDK, please take a few minutes to read the documents in <ndk>/docs/ directory, especially OVERVIEW.html and CPU-X86.html, so that you understand the NDK mechanism and how to use it.

NDK application development can be divided into five steps shown in Figure 3:

Figure 3: NDK Application Development Process

The hello-jni demo is used to illustrate these five steps. You can find the demo in your NDK Rootsampleshello-jni folder [5]. Hello-jni demo is a simple application included in the NDK that get a string from a native method in a shared library and uses it in the application UI.

3.1.1. Create native code

Create a new Android project and place your native source code under <project>/jni/. The project content is shown in Figure 4. This demo includes a simple function in native code called Java_com_example_hellojni_HelloJni_stringFromJNI(). As shown in the source code, it returns a simple string from JNI.

Figure 4: Create Native Code

3.1.2 Create MakeFile ‘Android.mk’

NDK applications are built for the ARM platform by default. To build NDK applications for the Intel Atom platform, you need to add APP_ABI := x86 into the MakeFile.

Figure 5: Create MakeFile

3.1.3 Compile native code

Build native code by running the ‘ndk-build’ script from the project’s directory. It is located in the top-level NDK directory. The result is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Compiled native code

The build tools automatically copy the stripped shared libraries to the proper location in the application’s project directory.

3.1.4 Call native code from Java

When you deploy the shared library successfully, you can call the function from Java side. The code is shown in Figure 7. A public native function call stringFromJNI() is created in Java code, and this function loads the shared library using System.loadlibrary().

Figure 7: Call native code from Java

3.1.5 Debug with GDB

If you want to debug the NDK application with GDB, the following conditions must be satisfied:

-

NDK application is built with ‘ndk-build’

-

NDK application is set to ‘debuggable’ in Android.manifest

-

NDK application is run on Android 2.2 (or higher)

-

Only one target is running

-

Add adb’s directory to PATH

Use the ndk-gdb command to debug the application. You can either set a breakpoint or a step-by-step debug to track the change history of a variable value as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Debug NDK application with GDB

3.2 Porting Existing NDK Applications to Intel Atom Processor-Based Devices

In this section, it is assumed that you have an Android application for the ARM platform and that you need to port it before deploying it on the Intel Atom platform.

Porting Android applications to the Intel Atom platform is similar to the development process. The steps are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9: Port Android applications to the Intel Atom platform

3.2.1 Port Dalvik applications

Dalvik applications can run on Intel Atom processor-based devices directly. The user interface needs to be adjusted for the target device. For a high resolution device, such as tablets with a 1280*800 resolution or higher, default memory allocation may not meet the application requirements, which results in the inability to launch the application. Increasing the default memory allocation is recommended for high resolution devices.

3.2.2 Port Android NDK applications

Porting NDK applications is a bit more complicated than porting Dalvik applications. All NDK applications can be divided into three types based on the following properties of the native code:

-

Consists of C/C code only that is not related to hardware

-

Uses a third-party dynamic linked library

-

Includes assembly code that is highly related to non-IA platforms

Native code that consists of C/C code only that is not related to hardware

-

Recompile the native code to run the application on the Intel Atom platform successfully.

-

Open the NDK project and search for Android.mk file and add APP_ABI := armeabi armeabi-v7a x86 in Android.mk and re-build the native code with ndk-build.

-

If the Android.mk file is not found, use the ndk-build APP_ABI=”armeabi armeabi-v7a x86″ command to build the project.

-

Package the application again with supported x86 platforms.

If native code uses a third-party dynamic linked library, the shared library must be recompiled into x86 version for the Intel Atom platform.

If native code includes assembly code that is highly related to non-IA platforms, code must be rewritten with IA assembly or C/C .

4.1 Forced Memory Alignment

Because of differences among architectures, platforms, and compilers, data sizes of the same data structure on different platforms may be different. Without forced memory alignment, there may be loading errors for inconsistent data size. [2]

The following example explains data sizes of the same data structure on different platforms:

struct TestStruct {

int mVar1;

long long mVar2;

int mVar3;

};

This is a simple struct with three variables called mVar1, mVar2, and mVar3.

mVar1 is an int, and it will cost 4 bytes

mVar2 is long long int which will cost 8 bytes

mVar3 is also int, it will cost 4 byte.

How many spaces are needed on the ARM and Intel Atom platforms?

The size of the data compiled for ARM and Intel Atom platforms with a default compiler switch is shown in Figure 10. ARM automatically adopts double malign and occupies 24 bytes, while x86 occupies 16 bytes.

Figure 10: Memory allocated by default compile flags

The 8-byte (64-bit) mVar2 results in a different layout for TestStruct because ARM requires 8-byte alignment for 64-bit variables like mVar2. In most cases, this does not cause problems because building for x86 vs. ARM requires a full rebuild.

However, a size mismatch could occur if an application serializes class or structures. For example, you create a file in an ARM application and it writes TestStruct to a file. If you later load the data from that file on an x86 platform, the class size in the application is different in the file. Similar memory alignment issues can occur for network traffic that expects a specific memory layout.

The GCC compiler option “-malign-double” generates the same memory alignment on x86 and ARM.

Figure 11: Memory allocated when -malign-double flags are added

4.2.1 NEON

The ARM NEON* technology is primarily used in multimedia such as smartphones and HDTV applications. According to ARM documentation, its 128 bit SIMD engine–based technology, which is an ARM Cortex*–A Series extension, has at least 3x performance over ARMv5 architecture and at least 2x over the follow-on, ARMv6. For more information on NEON technology visit: http://www.arm.com/products/processors/technologies/neon.php.

4.2.2 SSE: The Intel equivalent

SSE is the Streaming SIMD Extension for Intel Architecture (IA). The Intel Atom processor currently supports SSSE3 (Supplemental Streaming SIMD Extensions 3) and earlier versions, but does not yet support SSE4.x. SSE is a 128-bit engine that handles the packing of floating-point data. The execution model started with the MMX technology, and SSx is essentially the newer generation replacing the need for MMX. For more information, refer to the “Volume 1: Basic Architecture” section of the Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manuals. The SSE overview, in section 5.5, provides the instructions for SSE, SSE2, SSE3, and SSSE3. These data operations move packed, precision-based floating point values between XMM registers or between XMM registers and memory. XMM registers are intended to be used as a replacement for MMX registers.

4.2.3 NEON to SSE at the assembly level

While using the IA Software Developer Manual as a cross-reference for all the individual SSE(x) mnemonics, also take a look at various SSE assembly-level instructions located at: http://neilkemp.us/src/sse_tutorial/sse_tutorial.html. Use the table of contents to access code samples or peruse the background information.

Similarly, the following manual from ARM provides information about NEON and contains small assembly snippets in section 1.4,”Developing for NEON”:http://infocenter.arm.com/help/topic/com.arm.doc.dht0002a/DHT0002A_introducing_neon.pdf.

Key differences when comparing NEON and SSE assembly code:

-

Endian-ness. Intel only supports little-endian assembly, whereas ARM supports big or little endian order (ARM is bi-endian). In the code examples provided, the ARM code is little-endian similar to Intel. Note: There may be some ARM compiler implications. For example, compiling for ARM using GCC includes flags –mlittle-endian and –mbig-endian. For more information refer to http://gcc.gnu.org/onlinedocs/gcc/ARM-Options.html.

-

Granularity. In the case of the simple assembly code examples referenced, compare the ADDPS instructions for SSE (Intel) with VADD.ix for NEON such as x = 8 or 16. Notice that the latter puts some granularity on the data to be handled as part of the mnemonic referenced.

Note: These differences are not all-inclusive. You may see other differences between NEON and SSE.

4.2.4 NEON to SSE at the C/C level

There are many API nuisances that may occur when porting C/C and NEON code to SSE. Keep in mind the assumption is that inline assembly is not being used, but rather, true C/C code is being used. NEON instructions also supply some native C libraries. Although these instructions are C code, they cannot be executed on the Intel Atom platform and must be rewritten.

5.1 Performance Tuning

During the coding process, use the following methods to optimize your application performance on the Intel Atom Platform.

5.1.1 Use Inline instead of Frequently Used Short

Inline functions are best used for small functions such as accessing private data members. Short functions are sensitive to the overhead of function calls. Longer functions spend proportionately less time in the calling/returning sequence and benefit less from inlining. [4]

The Inline function saves overhead on:

-

Function calls (including parameter passing and placing the object’s address on the stack)

-

Preservation of caller’s stack frame

-

New stack-frame setup

-

Return-value communication

-

Old stack-frame restore

-

Return

5.1.2 Use Float instead of Double

FPU is a floating-point unit that is a part of a computer system specially designed to carry out operations on floating point numbers, such as: addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and square root. Some systems (particularly older, microcode-based architectures) can also perform various transcendental functions such as exponential or trigonometric calculations. Current processors perform these calculations with software library routines. In most modern general purpose computer architectures, one or more FPUs are integrated with the CPU [6].

The Intel Atom platform has FPU enabled. In most cases, using Float instead of Double speeds up the data computing process and saves memory bandwidth in Intel Atom processor-based devices.

5.1.3 Multi-thread coding

Multi-thread coding allows you to use the hyper-threading function of the Intel Atom processor to increase throughput and improve overall performance. For more information about multi-threading, refer to: http://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/architecture-and-technology/hyper-threading/hyper-threading-technology.html.

5.2 Building High Performance Applications with Compiler Flags

As you know, native code is built by GCC in Android applications. But do you know the default target device of GCC? It is the Pentium® Pro processor. Targeted binary code runs best on the Pentium Pro platform if you do not add any flags when compiling your native code. Most Android applications run on the Intel Atom platform instead of Pentium Pro. Adding specific flags according to your target platform is highly recommended. You can add the following recommended flags during compilation on the Intel Atom platform:

-march=atom

-msse4

-mavx

-maes

For more information about compiler parameters, refer to: http://gcc.gnu.org/onlinedocs/gcc/i386-and-x86-64-Options.html

This document discusses how to develop and optimize Android applications on Intel Atom platforms, as well as how to develop and port NDK applications.

A summary of the key points include:

-

Most Android applications can execute on the Intel Atom platform directly. NDK applications need to recompile native code. If assembly code is included in the application, this portion of the code must be rewritten.

-

Make full use of IA (Intel Architecture) features to improve your Android application performance.

-

Add platform-specific compile switches to make the GCC build code more effective.